|

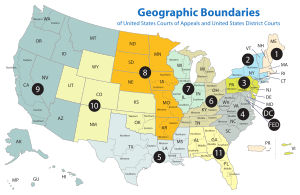

| Map of the geographic boundaries of the various United States Courts of Appeals and United States District Courts. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

In the previous posts in this series, we have introduced you to the requirement of FAPE. In this installment, we discuss the separate but equally important requirement of LRE.

The Requirement of LRE (least restrictive environment)

people are surprised to learn that IDEA does not mention the word "mainstreaming." IDEA does require, however, that to the “…maximum extent appropriate, children with disabilities … are educated with children who are not disabled, and special classes, separate schooling or other removal of children with disabilities from the regular education environment occurs only when the nature or severity of the disability of a child is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily.” IDEA, § 612(a)(5). See, 34 C.F.R. §§ 300.114 to 300.119.

The Supreme Court has not yet ruled on the issue of LRE, but a number of Circuit Courts of appeal have provided some guidance. For example, the Fifth Circuit has developed a two pronged analysis: the first question is whether education of the student with a disability in the regular classroom, with the use of supplemental aids and services, can be satisfactorily achieved, and if it cannot, whether the school district has provided the student with interaction with non-disabled peers to the maximum extent appropriate. Daniel RR v. State Board of Education 874 F.2d 1036, 441 IDELR 433 (5th Cir. 1989).

The Ninth Circuit has developed four factors which must be balanced to determine the LRE placement: (1) the educational benefits available to the student in a regular classroom, supplemented with appropriate aids and services, as compared with the educational benefits of a special education classroom; (2) the non-academic benefits of interaction with children who were not disabled; (3) the effect of the student's presence on the teacher and other children in the classroom; and (4) the cost of mainstreaming the student in a regular classroom. Sacramento City Sch Dist v. Rachel H by Holland 14 F.3d 1398, 20 IDELR 812 (9th Cir. 01/24/1994).

The Fourth Circuit has stated the rule this way: “The Act's language obviously indicates a strong congressional preference for mainstreaming. Mainstreaming, however, is not appropriate for every handicapped child …The proper inquiry is whether a proposed placement is appropriate under the Act. In some cases, a placement which may be considered better for academic reasons may not be appropriate because of the failure to provide for mainstreaming… In a case where the segregated facility is considered superior, the court should determine whether the services which make that placement superior could be feasibly provided in a non-segregated setting. If they can, the placement in the segregated school would be inappropriate under the Act. Framing the issue in this manner accords the proper respect for the strong preference in favor of mainstreaming while still realizing the possibility that some handicapped children simply must be educated in segregated facilities either because the handicapped child would not benefit from mainstreaming, because any marginal benefits received from mainstreaming are far outweighed by the benefits gained from services which could not feasibly be provided in the non-segregated setting, or because the handicapped child is a disruptive force in the non-segregated setting.” DeVries v. Fairfax County Sch Bd 882 F.2d 876, 441 IDELR 555 (Fourth Cir. 1989)

LRE and FAPE are the twin towers of special education law.